Self_notes_android_security

Hey Readers,

This section discusses the notes that I have come across while reading multiple books about Android internals and Android security. I am writing this for to keep a track of the topics I have covered and a note to be used in future. However, you are free to use the resources if you want.

Update: Please note that this might not be the complete version at the time you are reading it and additional sections will be added as and when I get the time.

Android’s architecture

Android is an open source, Linux-based software stack created for a wide array of devices and form factors. The following diagram shows the major components of the Android platform.

Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)

The hardware abstraction layer (HAL) provides standard interfaces that expose device hardware capabilities to the higher-level Java API framework. The HAL consists of multiple library modules, each of which implements an interface for a specific type of hardware component, such as the camera or bluetooth module. When a framework API makes a call to access device hardware, the Android system loads the library module for that hardware component.

Android Runtime

For devices running Android version 5.0 (API level 21) or higher, each app runs in its own process and with its own instance of the Android Runtime (ART). ART is written to run multiple virtual machines on low-memory devices by executing DEX files, a bytecode format designed specially for Android that’s optimized for minimal memory footprint. Build tools, such as d8, compile Java sources into DEX bytecode, which can run on the Android platform.

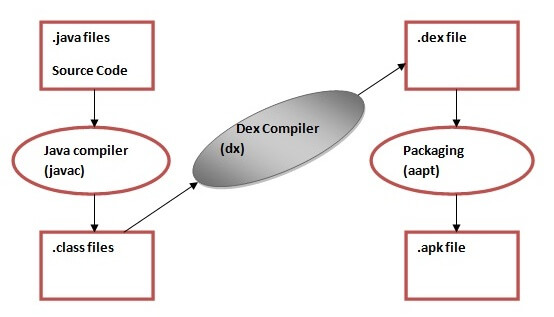

IMG:

Some of the major features of ART include the following:

- Ahead-of-time (AOT) and just-in-time (JIT) compilation

- Optimized garbage collection (GC)

- On Android 9 (API level 28) and higher, conversion of an app package’s Dalvik Executable format (DEX) files to more compact machine code.

- Better debugging support, including a dedicated sampling profiler, detailed diagnostic exceptions and crash reporting, and the ability to set watchpoints to monitor specific fields

Prior to Android version 5.0 (API level 21), Dalvik was the Android runtime. If your app runs well on ART, then it should work on Dalvik as well, but the reverse may not be true.

Android also includes a set of core runtime libraries that provide most of the functionality of the Java programming language, including some Java 8 language features, that the Java API framework uses.

Ref: https://developer.android.com/guide/platform#linux-kernel

Difference b/w JIT and AOT

Just In Time (JIT):

With the Dalvik JIT compiler, each time when the app is run, it dynamically translates a part of the Dalvik bytecode into machine code. As the execution progresses, more bytecode is compiled and cached. Since JIT compiles only a part of the code, it has a smaller memory footprint and uses less physical space on the device.

Ahead Of Time (AOT):

ART is equipped with an Ahead-of-Time compiler. During the app’s installation phase, it statically translates the DEX bytecode into machine code and stores in the device’s storage. This is a one-time event which happens when the app is installed on the device.

Android N includes a hybrid runtime:

There won’t be any compilation during install, and applications can be started right away, the bytecode being interpreted. There is a new, faster interpreter in ART and it is accompanied by a new JIT, but the JIT information is not persisted. Instead, the code is profiled during execution and the resulted data is saved.

Benefits of ART:

- Apps run faster as DEX bytecode translation done during installation.

- Reduces startup time of applications as native code is directly executed.

- Improves battery performance as power utilized to interpreted byte codes line by line is saved.

- Improved garbage collector.

Drawbacks of ART:

-

App Installation takes more time because of DEX bytecodes conversion into machine code during installation.

-

As the native machine code generated on installation is stored in internal storage, more internal storage is require

Ref: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/40336455/difference-between-aot-and-jit-compiler-in-the-art

Odex versus Deodex

One commonly occurring word when playing with custom ROMs and firmware, and even themes is deodexed and odexed. Most users fail to understand what these terms actually imply, and while developers would boast again and again about their themes and ROMs being deodexed, the average user is left clueless as to what is going on.

What is an .odex file?

In Android file system, applications come in packages with the extension .apk. These application packages, or APKs contain certain .odex files whose supposed function is to save space. These ‘odex’ files are actually collections of parts of an application that are optimized before booting. Doing so speeds up the boot process, as it preloads part of an application. On the other hand, it also makes hacking those applications difficult because a part of the coding has already been extracted to another location before execution.

Then comes deodex!

Deodexing is basically repackaging of these APKs in a certain way, such that they are reassembled into classes.dex files. By doing that, all pieces of an application package are put together back in one place, thus eliminating the worry of a modified APK conflicting with some separate odexed parts.

In summary, Deodexed ROMs (or APKs) have all their application packages put back together in one place, allowing for easy modification such as theming. Since no pieces of code are coming from any external location, custom ROMs or APKs are always deodexed to ensure integrity.

How this works

For the more geeky amongst us, Android OS uses a Java-based virtual machine for running applications, called the Dalvik Virtual Machine. A deodexed, or .dex file contains the cache used by this virtual machine (referred to as Dalvik-cache) for a program, and it is stored inside the APK. An .odex file, on the other hand, is an optimized version of this same .dex file that is stored next to the APK as opposed to inside it. Android applies this technique by default to all the system applications.

Now, when an Android-based system is booting, the davlik cache for the Davlik VM is built using these .odex files, allowing the OS to learn in advance what applications will be loaded, and thus speeds up the booting process.

By deodexing these APKs, a developer actually puts the .odex files back inside their respective APK packages. Since all code is now contained within the APK itself, it becomes possible to modify any application package without conflicting with the operating system’s execution environment.

Advantages & Disadvantages

The advantage of deodexing is in modification possibilities. This is most widely used in custom ROMs and themes. A developer building a custom ROM would almost always choose to deodex the ROM package first, since that would not only allow him to modify various APKs, but also leave room for post-install theming.

On the other hand, since the .odex files were supposed to quickly build the dalvik cache, removing them would mean longer initial boot times. However, this is true only for the first ever boot after deodexing, since the cache would still get built over time as applications are used. Longer boot times may only be seen again if the dalvik cache is wiped for some reason.

For a casual user, the main implication is in theming possibilities. Themes for android come in APKs too, and if you want to modify any of those, you should always choose a dedoexed custom ROM.

Ref: https://forum.xda-developers.com/t/explained-difference-between-odex-and-deodex.2224570/

Dalvik VM

- Dalvik VM is a (register based) android virtual machine optimized for mobile devices.Dalvik was designed with mobile devices in mind and cannot run Java bytecode (.class files) directly.Its native input format is called Dalvik Executable (DEX) and is packaged in .dex files. In turn, .dex files are packaged either inside system Java libraries (JAR files), or inside Android applications.

Note: Dalvik and Oracle’s JVM have different architectures—register-based in Dalvik versus stack-based in the JVM.Register-based models are good at optimizing and running on low memory. They can store common sub-expression results which can be used again in the future. This is not possible in a Stack-based model at all. Dalvik Virtual Machine uses its own byte-code and runs “.dex”(Dalvik Executable File) file.

img:

Advantages

- DVM supports the Android operating system only.

- In DVM executable is APK.

- Execution is faster.

- From Android 2.2 SDK Dalvik has it’s own JIT (Just In Time) compiler.

- DVM has been designed so that a device can run multiple instances of the Virtual Machine effectively.

- Applications are given their own instances.

Disadvantages

- DVM supports only Android Operating System.

- For DVM very few Re-Tools are available.

- Requires more instructions than register machines to implement the same high-level code.

- App Installation takes more time due to dex.

- More internal storage is required.

Ref: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/what-is-dvmdalvik-virtual-machine/

Java Runtime Environment (JRE)

The Java Runtime Environment (JRE) provides the libraries, the Java Virtual Machine, and other components to run applets and applications written in the Java programming language. In addition, two key deployment technologies are part of the JRE: Java Plug-in, which enables applets to run in popular browsers; and Java Web Start, which deploys standalone applications over a network. It is also the foundation for the technologies in the Java 2 Platform, Enterprise Edition (J2EE) for enterprise software development and deployment. The JRE does not contain tools and utilities such as compilers or debuggers for developing applets and applications.

Java Development Kit (JDK)

The JDK is a superset of the JRE, and contains everything that is in the JRE, plus tools such as the compilers and debuggers necessary for developing applets and applications.

JVM

The Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is the virtual machine that runs the Java bytecodes. The JVM doesn’t understand Java source code; that’s why you need compile your *.java files to obtain *.class files that contain the bytecodes understood by the JVM. It’s also the entity that allows Java to be a “portable language” (write once, run anywhere). Indeed, there are specific implementations of the JVM for different systems (Windows, Linux, macOS, see the Wikipedia list), the aim is that with the same bytecodes they all give the same results.

Ref: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/11547458/what-is-the-difference-between-jvm-jdk-jre-openjdk

Java Native Interface (JNI)

JNI is the Java Native Interface. It defines a way for the bytecode that Android compiles from managed code (written in the Java or Kotlin programming languages) to interact with native code (written in C/C++). JNI is vendor-neutral, has support for loading code from dynamic shared libraries, and while cumbersome at times is reasonably efficient.

Ref: https://developer.android.com/training/articles/perf-jni

Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

Android is a unix like system that have separate address spaces and a process cannot directly access another process’s memory (called process isolation).However, if a process wants to offer some useful service(s) to other processes, it needs to provide some mechanism that allows other processes to discover and interact with those services. That mechanism is referred to as IPC.These include files, signals, sockets, pipes, semaphores, shared memory, message queues, and so on. While Android uses some of these (such as local sockets), it does not support others (namely System VIPCs like semaphores, shared memory segments, and message queues)

For Andoid we have few of the below IPC mechanisms 1) Intents: These are messages which components can send and receive. It is a universal mechanism of passing data between processes. With help of the intents one can start services or activities, invoke broadcast receivers and so on.

2) Bundles: These are entities of data that is passed through. It is similar to the serialization of an object, but much faster on android. Bundle can be read from intent via the getExtras() method.

3) Binders: These are the entities which allow activities and services to obtain a reference to another service. It allows not simply sending messages to services but directly invoking methods on them. 4) ASHMEM (Anonymous Shared Memory) : The main difference between Linux shared memory and this shared memory is, in Linux other processes can’t free the shared memory but here if other processes require memory this memory can be freed by Android OS.

Ref: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/5740324/what-are-the-ipc-mechanisms-available-in-the-android-os/35450853

Android Framework Libraries

Android framework libraries, sometimes calledjust “the framework.” The framework includes all Java libraries that are not part of the standard Java runtime (java., javax., and so on) and is for the most part hosted under the android top-level package. The framework includes the basic blocks for building Android applications, such as the base classes for activities, services, and content providers (in the android.app.packages); GUI widgets (in the android.view. and android.widget packages);and classes for file and database access (mostly in the android.database.* and android.content.* packages). It also includes classes that let you interact with device hardware, as well as classes that take advantage of higher-level services offered by the system.

System Apps

System apps are included in the OS image, which is read-only on production devices (typically mounted as /system), and cannot be uninstalled or changed by users. Therefore, these apps are considered secure and are given many more privileges than user-installed apps. System apps can be part of the core Android OS or can simply be preinstalled user applications, such as email clients or browsers. While all apps installed under /system were treated equally in earlier versions of Android (except by OS features that check the app signing certificate), Android 4.4 and higher treat apps installed in /system/priv-app/ as privileged applications and will only grant permissions with protection level signature Or System to privileged apps, not to all apps installed under /system. Apps that are signed with the platform signing key can be granted system permissions with the signature protection level, and thus can get OS-level privileges even if they are not preinstalled under /system.While system apps cannot be uninstalled or changed, they can be updated by users as long as the updates are signed with the same private key, and some can be overridden by user-installed apps. For example, a user can choose to replace the preinstalled application launcher or input method with a third-party application.

User-Installed Apps

User-installed apps are installed on a dedicated read-write partition (typically mounted as /data) that hosts user data and can be uninstalled at will. Each application lives in a dedicated security sandbox and typically cannot affect other applications or access their data

Android’s security model

Android automatically assigns a unique UID/app ID to each applications at installations and executes that application in a dedicated process running as that UID.Thus they are said to be sandboxed or isolated,both at the process level (by having each run in a dedicated process) and at the file level (by having a private data directory). This creates a kernel-level application sandbox, which applies to all applications, regardless of whether they are executed in a native or virtual machine process.

Android does not have the traditional /etc/password file and its system UIDs are statically defined in the android_filesystem_config.h header file.UIDs for system services start from 1000, with 1000 being the system (AID_SYSTEM) user, which has special (but still limited) privileges.Automatically generated UIDs for applications start at 10000 (AID_APP), and the corresponding usernames are in the form app_XXX or uY_aXXX (on Android versions that support multiple physical users), where XXX is the offset from AID_APP and Y is the Android user ID (not the same as UID). Application UIDs are managed alongside other package metadata in the /data/system/packages.xml file (the canonical source) and also written to the /data/system/packages.list file

**Applications can be installed using the same UID, called a shared user ID, in which case they can share files and even run in the same process. Shared user IDs are used extensively by system applications, which often need to use the same resources across different packages for modularity. **

Note: While the shared user ID facility is not recommended for non-system apps, it’s available to third-party applications as well. In order to share the same UID, applications need to be signed by the same code signing key. Additionally, because adding a shared user ID to a new version of an installed app causes it to change its UID, the system disallows this. Therefore, a shared user ID cannot be added retroactively, and apps need to be designed to work with a shared ID from the start.

Android Permissions

Applications’ permissions are extracted from the application’s manifest at install time by the PackageManager and stored in /data/system/packages.xml The permission-to-group mappings are stored in /etc/permissions/platform.xml

Android Multi-User Support

Each user is assigned a unique user ID, starting with 0, and users are given their own dedicated data directory under /data/system/users/

Android SE-Linux Feature

Android uses Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) to enforce mandatory access control (MAC) over all processes, even processes running with root/superuser privileges (Linux capabilities). With SELinux, Android can better protect and confine system services, control access to application data and system logs, reduce the effects of malicious software, and protect users from potential flaws in code on mobile devices. SELinux operates on the principle of default denial: Anything not explicitly allowed is denied. SELinux can operate in two global modes: * Permissive mode, in which permission denials are logged but not enforced. * Enforcing mode, in which permissions denials are both logged and enforced. Android includes SELinux in enforcing mode and a corresponding security policy that works by default across AOSP. In enforcing mode, disallowed actions are prevented and all attempted violations are logged by the kernel to dmesg and logcat

Ref: https://source.android.com/security/selinux

# Android Package

# APK

APK : typically a zip/jar archieve (MIME type: application/vnd.android.package-archive)

apk/

|-- AndroidManifest.xml

|-- classes.dex

|-- resources.arsc:packages all of the application’s compiled resources such as strings and styles

|-- assets/x

|-- lib/y

| |-- armeabi/

| | `-- libapp.so

| `-- armeabi-v7a/

| `-- libapp.so

|-- META-INF/z

| |-- CERT.RSA

| |-- CERT.SF

| `-- MANIFEST.MF: package manifest file and code signatures

`-- res/{

|-- anim/

|-- color/

|-- drawable/

|-- layout/

|-- menu/

|-- raw/

`-- xml/

Note: Downloading app directly from some source and installing them is known as **sideloading ** of apps. Note: Usually system apps are located in /system/app while /system/priv-app holds privleged apps granted with permisson,likewise /system/vendor/app hosts vendor specific applications.User installed apps are located at /data/app.The userdata partition also hosts the optimized DEX files for user-installed applications (in /data/dalvik-cache/), the system package database (in /data/system/packages .xml), and other system databases and settings files.

# Signature Verification The first step is to check whether the new package has been signed by the same set of signers as the existing one. This rule is referred to as same origin policy, or Trust On First Use (TOFU). This signature check guarantees that the update is produced by the same entity as the original application (assuming that the signing key has not been compromised) and establishes a trust relationship between the update and the existing application.

# Encrypted APKs

Encrypted APKs can be installed using the Google Play Store client, or with the pm command from the Android shell, but the system PackageInstaller does not support encrypted APKs.

adb install [-l] [-r] [-s] [–algo

Note: SDCard uses FAT file system which lacks permission.So encrypted apks are stored using mounted using Android Secure External Caches, or ASEC containers. ASEC container management (creating, deleting, mounting, and unmounting) is implemented in the system volume daemon (vold), and the MountService provides an interface to its functionality to framework services.

# ls -l /mnt/asec/com.example.app-1

drwxr-xr-x system system lib

drwx------ root root lost+found

-rw-r----- system u0_a96 1319057 pkg.apk

-rw-r--r-- system system 526091 res.zip

Here, the res.zip holds app resources and the manifest file and is world readable, while the pkg.apk file that holds the full APK is only readable by the system and the app’s dedicated user (u0_a96). The actual app containers are stored in /data/app-asec/ in files with the .asec extension.

# Foward Locking Mechanism To prevent users from simply copying paid apps from the SD card, Android 2.2 created an encrypted filesystem image file and stored the APK in it when a user opted to move an app to external storage. The system would then create a mount point for the encrypted image, and mount it using Linux’s device-mapper. Android loaded each app’s files from its mount point at runtime. Android 4.1 built on this idea by making the container use the ext4 filesystem, which allows for file permissions

# ls -l /mnt/asec/com.example.app-1

drwxr-xr-x system system lib

drwx------ root root lost+found

-rw-r----- system u0_a96 1319057 pkg.apk

-rw-r--r-- system system 526091 res.zip

We can also use the vdc command-line utility to interact with vold in order to manage forward-locked apps from Android’s shell.

# vdc asec listu

vdc asec list

111 0 com.example.app-1

111 0 org.foo.app-1

200 0 asec operation succeeded

# vdc asec path com.example.app-1v

vdc asec path com.example.app-1

211 0 /mnt/asec/com.example.app-1

# Android User MetaData

Android stores user data in the /data/system/users/ directory that hosts

metadata about users in XML format, as well as user directories. On a

device with five users, its contents may look like Listing

# ls -lF /data/system/users

drwx------ system system 0u

-rw------- system system 230 0.xmlv

drwx------ system system 10

-rw------- system system 245 10.xml

# Device Security A bootloader is a specialized, hardware-specific program that executes when a device is first powered on (coming out of reset for ARM devices). Its purpose is to initialize device hardware, optionally provide a minimal device configuration interface, and then find and start the operating system. # Recovery In Android, recovery refers to the dedicated, bootable partition that has the recovery console installed. A combination of key presses (or instructions from a command line) will boot your phone to recovery, where you can find tools to help repair (recover) your installation as well as install official OS updates.

# There are two types of recovery mode.

** Stock Recovery — This is the official recovery installed on your android device.Each and every android device has Stock Recovery installed in it.You can find above mentioned functionalities in Stock Recovery , but note that Stock Recovery only allows official updates.You cant install unofficial updates or Custom ROM’s using Stock Recovery , because Stock Recovery always checks the file integrity, checksum along with signature before installing. ** Custom Recovery — If you need to install an Unofficial update or Custom ROM, you can’t use Stock Recovery because Unofficial things don’t have valid signature on it.Then you can replace your Stock Recovery with a matching Custom Recovery.Custom Recovery will install updates or ROM’s without checking the signature,but it will increase the possibilities of installing mismatching update on your device , which will brick it! If you still need to install a custom recovery, there are CWM(clockworkmod), TWRP (TeamWin Recovery Project) and CMRecovery(from CynogenMod) custom recoveries available for you!

# System On Chip (SoC) System-on-Chip (SoC) is the name given to a single piece of silicon that includes the CPU core, along with a graphics processing unit (GPU), random access memory (RAM), input/output (I/O) logic, and sometimes more.

Note: Android follows AID concept instead of traditionla unix like UID/GID.Though all AID entries map to both a UID and GID, the UID may not necessarily be used to represent a user on the system. For instance, AID_SDCARD_RW maps to sdcard_rw, but is used only as a supplemental group, not as a UID on the system.One can find definitions for AIDs in system/core/ include/private/android_filesystem_config.

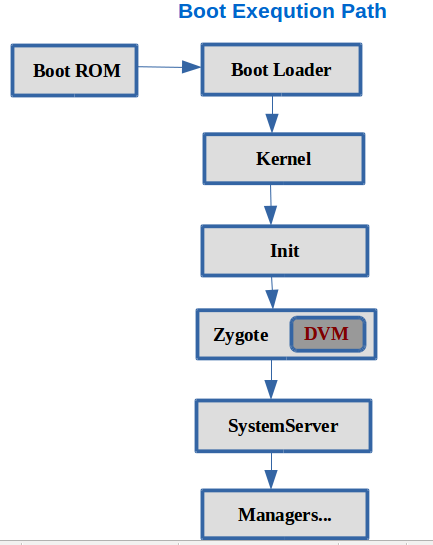

# Zygote

Ref: https://medium.com/android-news/android-boot-process-8f7d94ff9889

Zygote One of the first processes started when an Android device boots is the Zygote process. Zygote, in turn, is responsible for starting additional services and loading libraries used by the Android Framework. The Zygote process then acts as the loader for each Dalvik process by creating a copy of itself, or forking. This optimization prevents having to repeat the expensive process of loading the Android Framework and its dependencies when starting Dalvik processes (including apps). As a result, core libraries, core classes, and their corresponding heap structures are shared across instances of the DalvikVM. Zygote’s second order of business is starting the system_server process. This process holds all of the core services that run with elevated privileges under the system AID. NOTE: The system_server process is so important that killing it makes the device appear to reboot. However, only the device’s Dalvik subsystem is actually rebooting.

Note: Fastboot is the standard Android protocol for flashing full disk images to specific partitions over USB. The fastboot client utility is a command-line tool

# Binary Exploiation

Ref: https://infosecwriteups.com/got-overwrite-bb9ff5414628 https://tripoloski1337.github.io/ctf/2020/06/11/format-string-bug.html

No eXecute (NX Bit):The No eXecute or the NX bit (also known as Data Execution Prevention or DEP) marks certain areas of the program as not executable, meaning that stored input or data cannot be executed as code. This is significant because it prevents attackers from being able to jump to custom shellcode that they’ve stored on the stack or in a global variable.

Relocation Read-Only (RELRO):Relocation Read-Only (or RELRO) is a security measure which makes some binary sections read-only.

There are two RELRO “modes”: partial and full. -Partial RELRO:Partial RELRO is the default setting in GCC, and nearly all binaries you will see have at least partial RELRO.

From an attackers point-of-view, partial RELRO makes almost no difference, other than it forces the GOT to come before the BSS in memory, eliminating the risk of a buffer overflows on a global variable overwriting GOT entries. Full RELRO

Full RELRO makes the entire GOT read-only which removes the ability to perform a “GOT overwrite” attack, where the GOT address of a function is overwritten with the location of another function or a ROP gadget an attacker wants to run.Full RELRO is not a default compiler setting as it can greatly increase program startup time since all symbols must be resolved before the program is started. In large programs with thousands of symbols that need to be linked, this could cause a noticable delay in startup time.

Tip: PLT is stored in code segment, hence is readable & executable, whereas GOT is stored in data segment, hence is readable & writable.

Stack Canaries: Stack Canaries are a secret value placed on the stack which changes every time the program is started. Prior to a function return, the stack canary is checked and if it appears to be modified, the program exits immeadiately.

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR): Address Space Layout Randomization (or ASLR) is the randomization of the place in memory where the program, shared libraries, the stack, and the heap are. This makes can make it harder for an attacker to exploit a service, as knowledge about where the stack, heap, or libc can’t be re-used between program launches. This is a partially effective way of preventing an attacker from jumping to, for example, libc without a leak.

Typically, only the stack, heap, and shared libraries are ASLR enabled. It is still somewhat rare for the main program to have ASLR enabled, though it is being seen more frequently and is slowly becoming the default.

DEP: DEP marks certain areas in memory (typically the user-writable parts) as non-executable so that attempts to execute code in these regions would cause an exception.